The Traumatized Brain

Trauma can take on many forms and can occur at any point in one’s life. Whether physical or emotional, trauma leaves behind scars that influence the decisions people make throughout their lifetime. But what is trauma exactly? There are hundreds of ways to describe trauma, and each individual defines it in their own way based on deep, personal experiences.

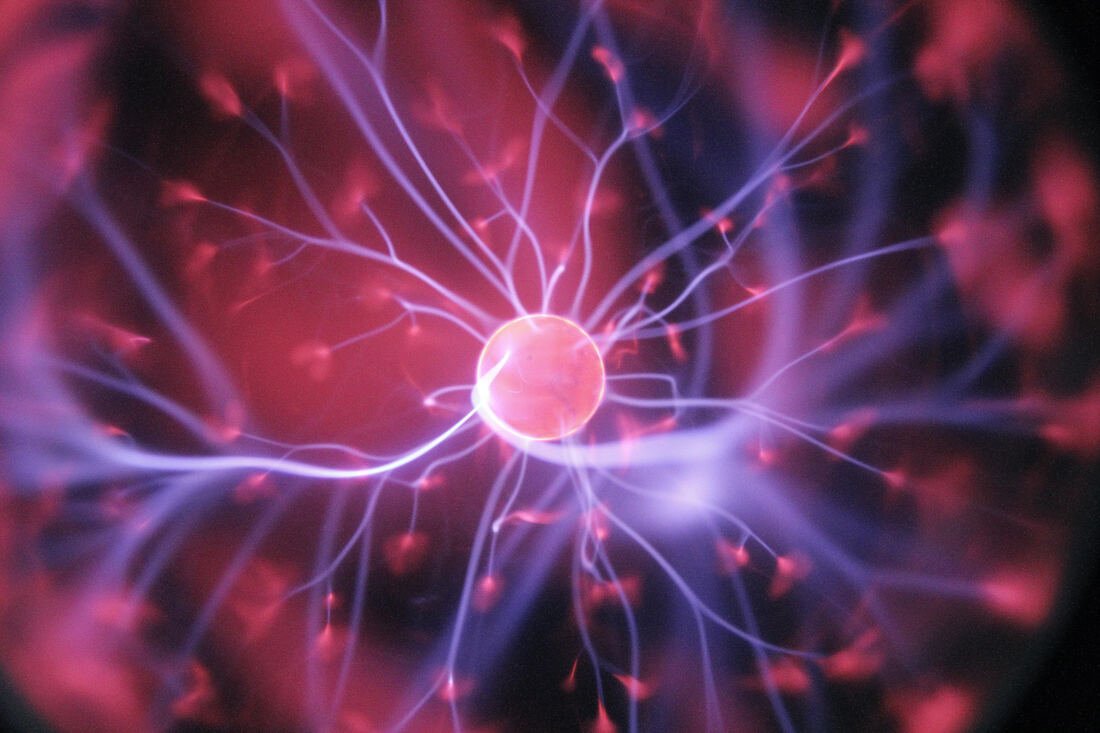

Before we dive into how trauma and the brain interact, lets remember our cast of characters from our previous posts: the pre-frontal cortex (PFC) and the limbic system. These two characters are responsible for the harmonization between our emotional and rational selves. The PFC is the part of our brain that helps us problem solve, make rational decisions, and perform many of the tasks we are required to do in our day to day lives at work or at school. The limbic system is a complex network of smaller structures that aids in our fight or flight response, allows us to connect to other humans on an emotional level, and is responsible for our emotional responses to stressors. Both the PFC and the limbic system are connected in the brain through “highways” of neuronal connections and send a constant stream of information to each other. This communication enables humans to have both an emotional and a logical response to a problem.

We will come back to our characters in a moment. For now, lets break down the word “trauma” and understand how the word will be defined in this post.

The Oxford Dictionary defines trauma as “a deeply distressing or disturbing experience” and an “emotional shock following a stressful event or a physical injury, which may be associated with physical shock and sometimes leads to long-term neurosis.” While these definitions are correct, they leave quite a bit of gray area and are open for various interpretations. In this post, we will define trauma using some of the descriptors from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The DSM-5 describes trauma as an “exposure to a traumatic event” such as war (as a combatant or civilian), threatened or actual physical assault or sexual violence, being kidnapped, taken hostage, terrorist attack, natural or man-made disasters, and severe motor vehicle accidents. This is certainly not an exhaustive list; however, it begins to identify some of the common traumatic experiences many people are exposed to.

So, what happens when a person experiences one of these events?

From a biological level, a response to a traumatic event is the same as a response to a “stressor.” A stressor, simply put, is an event or situation that brings about feelings of overwhelm, anxiety, worry, fear, or sadness. This response is systemic; the entire human body, not just the brain, responds to the stressor. A surge of hormones and neurotransmitters instruct our body on how to respond. Muscles tense, the heart beats faster, breathing rate increases, pupils dilate…and the flood of adrenaline prepares our bodies to fight, flee, or freeze.

While our bodies prepare to respond to the stressor, the brain fires on all cylinders with one goal in mind: self-preservation. In a matter of milliseconds, the brain processes information from the five senses and decides what needs to be done to protect us from harm. In these few moments, the brain coordinates an entire action plan, and we operate out of pure survival mode.

Here is an example: you are driving along the highway, listening to your favorite song on the radio. Out of nowhere, a truck in front of you blows a tire, and the tread comes flying down the road right in front of you. All of the sudden, you swerve your car out of the way, somehow missing the car in the lane next to you. You swerve back into your lane as the truck pulls out of the way. In less than three seconds, you are driving down the highway again and tune back in to the next verse of the song without missing a beat. Once you realize what just happened, you feel the adrenaline rush and think to yourself “wow, that could have been bad!” Perhaps you take a few deep breaths to calm down your heart rate, and in a few more minutes, its as if nothing happened.

However, in those three seconds, your brain and your body seem to have taken over all conscious thought. Was it really you who maneuvered the car every so skillfully to avoid a collision? Sometimes it feels as though another power takes over in these moments; your body is just along for the ride and time passes more slowly.

In those split seconds, the human brain enters into self-preservation mode. This is where the PFC and limbic system characters make their entrance.

The PFC, again, is responsible for logical, rational decision making. But the PFC is slow. He takes time to process through every situation, every outcome, every positive or negative ending to a decision. During the example of the car and narrowly avoiding an accident, the PFC was nowhere to be found. In this situation, the PFC does not have the time to undergo his normal deliberation process. By the time the PFC made up his mind to swerve left or right, the tread hit the car, causing the car to spin and crash into the median. But instead, the driver used just the right movements to steer the car out of harms way.

While the PFC sits with his play-by-play game cards, the limbic system has already processed hundreds of outcomes and chose the correct set of instructions to self-preserve. But how does the limbic system know what to do that quickly?

In order to answer this question, we need to dive deeper into the limbic system itself. The limbic system is divided into multiple sub-structures, including the thalamus, hippocampus, cingulate cortex, and the amygdala. Each structure has its own role and function, but for this topic, we will focus on the amygdala. This almond-shaped, small structure is commonly thought of as the “core system for processing fearful and threatening stimuli…including detection of threat and activation of appropriate fear-related behaviors in response to threatening or dangerous stimuli.” Based on this definition, it is no wonder why the amygdala, and its surrounding limbic system, is the main character in the face of trauma-inducing events.

The amygdala’s power resides in its ability to make split-second choices and send instructions to the rest of the body. Going back to our car example, the amygdala knew how to send signals to the right muscles to turn the wheel in a certain direction at a certain angle, calculate the near miss of the car in the next lane, and ensure the truck who blew the tire remained far enough way. These steps are a combination of memory and experience that the amygdala relies upon. In prior life situations, the amygdala learned what muscles control the fine movements required to operate a steering wheel and put them to action. The amygdala also tapped into memory storage to recall that a few seconds before the potential accident, there was another car in the driver’s blind spot seen during a routine side-mirror check. The combination of all of these little details led to the amygdala’s role in self-preservation and avoiding a traumatic accident.

Now there is a problem: the amygdala can sometimes make a mistake, or a traumatic event is inevitable. Recall the DSM-5 description of traumatic events. For example, a military combatant is ordered to charge into gunfire, or a large tornado desolates a town and its inhabitants. In both of these examples, the stressor/traumatic event is unavoidable. The solider is doing his or her job and has no choice but to face the stressor head on, regardless of the threat to his or her own safety. The town members cannot outrun a tornado but do their best to take shelter and hope that they and their loved ones survive.

In these cases, the amygdala, and the rest of the brain and body for that matter, have no choice but to fight, flee, or freeze. The amygdala does its best to communicate with the rest of the limbic system and the PFC to aid in self-preservation. But often times in such traumatic situations, there are lasting effects that leave survivors with emotional scars.

When the amygdala and limbic system are unable to self-preserve and a traumatic outcome occurs, these two systems can become “stuck” in a cycle of processing and re-processing the events that transpired. In day-to-day life, humans experience the manifestation of trauma-related symptoms in many forms: nightmares, panic attacks, sensitivity to certain stimuli (hypervigilance), withdrawal from people or places that remind them of the trauma, and even physical symptoms such as loss of appetite or fatigue. In the mental health and psychology world, professionals frequently classify these symptoms as indictors for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Following a traumatic event, the amygdala becomes overly taxed, and the normal fight or flight response is elevated. As the amygdala failed once before, it tries to avoid any situation that could cause additional harm. Let us take a war veteran as an example. While overseas, the solider was ordered to charge into oncoming artillery fire to aid in a rescue mission. During the charge, the solider was exposed to loud gunfire, smoke, fellow soldiers being shot and killed, and fear of being shot himself. While the mission may have been an overall success, the soldier lost a friend who he was unable to save on the field. A few months later, the solider is safely back home and trying to host a birthday party for his daughter when a party balloon pops. This loud noise sounded eerily similar to the gunfire he heard months before; the same gunfire that killed his fellow soldier and friend. Without warning, he leaps from his chair and grabs his daughter, fleeing into the other room. Other party attendees may be confused as to what happened and why he seemed to overreact to just a balloon. However, this veteran’s amygdala and limbic system are still entangled in a cycle of trauma that was unresolved months before. Only this time, there was no actual threat – just a perceived one that he instinctively reacted to in order to keep his loved one safe. The body and the brain remember the trauma long after the event occurs.

This fictional example is all too real for many veterans returning home. The amygdala is still living in a world where danger can come from any direction and cannot differentiate between what happened then and what is happening now. To the amygdala and limbic system, the traumatic event is starting all over again.

It is this cycle that leads to a traumatized brain. With an overreactive and exhausted amygdala, the entire limbic system is thrown into chaos. Without a properly regulated limbic system, the PFC struggles to make logical decisions and its process is frequently overridden with fight or flight instincts. In a cycle of trauma and ongoing PTSD, the PFC almost seems to take a backseat, and the limbic system has full control in the name of self-preservation.

The good news is that breaking this cycle can be done. With a correct evaluation and a PTSD diagnosis, many individuals can overcome their trauma and rewire their limbic systems to live a more peaceful life. One of the most common therapeutic interventions for PTSD is called Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. EMDR was initially developed in the 1980’s and has been used almost exclusively for PTSD. In a nutshell, EMDR works to process through memories that contain the emotions, thoughts, beliefs, and physical sensations that occurred at the time of the traumatic event. This process facilitates in fear extinction and aids memory condition - the memory can then be re-processed with lower levels of physiological arousal. During a structured EMDR therapy session, the therapist leads the patient through the traumatic memories to reprocess, relabel, and redefine the trauma. In other words, breaking the cycle.

The office of Hilary Morris, LPC specializes in trauma-work and trauma reprocessing. Hilary Morris, LPC and Mary Aragon, LPC, LAC are trained EMDR therapists and have been using this evidence-based approach for many years. While EMDR is not for everyone, it can certainly be something to discuss with a doctor or mental health counselor with the appropriate training. In addition to EMDR, many patients with PTSD may try various psychiatric medications to aid in symptom management. These recommendations are given by a psychiatrist.

For additional information on PTSD, please follow these helpful resources below: